Behind the curtains hide the dolls.

Well, not dolls, really. Figurines: a troll, a tiny Buddha, a few small ceramic statues, a handmade fellow of clay. They stand in a line most of the time, as if ready to bow when Lacy opens the curtains. Dutifully, Lacy feeds each every day (small blades of grass) and lays them down each night (some under a Kleenex blanket).

And, when the curtain opens and there’s no grass to eat, no sleep to sleep, the figurines stare. Lacy stares back.

Then, with somber intent, Lacy closes the curtains and goes about her summer.

Ah, the summer. The summer of 1991, before 11-year-old Lacy heads to friendless middle school. A summer of ice cream. Of piano lessons. Of hot evenings beside the home’s spinning fans.

Another precious summer with her precious mother, Janet, in backwoods Massachusetts.

A summer with her mother’s friends.

Unlike Lacy, Janet has many friends. But they seem to come in ones.

First, Wayne, Janet’s taciturn boyfriend. Long stares. Grunts at dinner. Perhaps, if he’s feeling particularly chatty, five or six words strung together.

Next, Regina. A friend from Janet’s distant past—back after all this time, trying to get on her feet and offer advice and use her sweet-smelling shampoo in Janet’s shower.

And Avi. Regina’s old boyfriend. Theater troupe leader. Possibly cult founder. He braids metaphysics and religion and spools it out like dental floss.

Lacy watches them all, as if they were figurines on her shelf. They speak. Laugh. Drink. Dance.

And Janet’s at the center, always at the center.

At least, at the center for Lacy.

If Janet is a planet, Lacy is her moon, circling ‘round and ‘round. Friends may come and go, like comets through the night. But Lacy and Janet, Janet and Lacy, they’ve been together forever and before. And so Lacy hopes it will last forever, whirling through the dark universe hand in hand, as close as two strangers can be.

You’ll not find much heroic virtue in Janet Planet; no one risks a life or blows a whistle or saves a planet. Even clear motivations or defined goals have no obvious place in this quiet, deceptively desperate film.

But like Lacy, our “Positive Elements” section must, in some fashion, still orbit around Janet.

Lacy is clearly not the easiest girl to raise, but Janet’s been raising her—and raising her largely alone—for more than 11 years. She is patient and kind. And even though she clearly can be frustrated with her daughter at times (as any mother can be with her own children), Janet’s always in her corner.

We hear hints of how hard Janet has had to work to become the successful single mother she is too. Janet intimates that, not so long ago, she would’ve been unable to support her and Lacy. But now she has her own business as an acupuncturist. (We’ll have more to say about acupuncture in the next section, though.) And she sincerely wants to help people—allowing her friend Regina, for instance, to stay with her for a time.

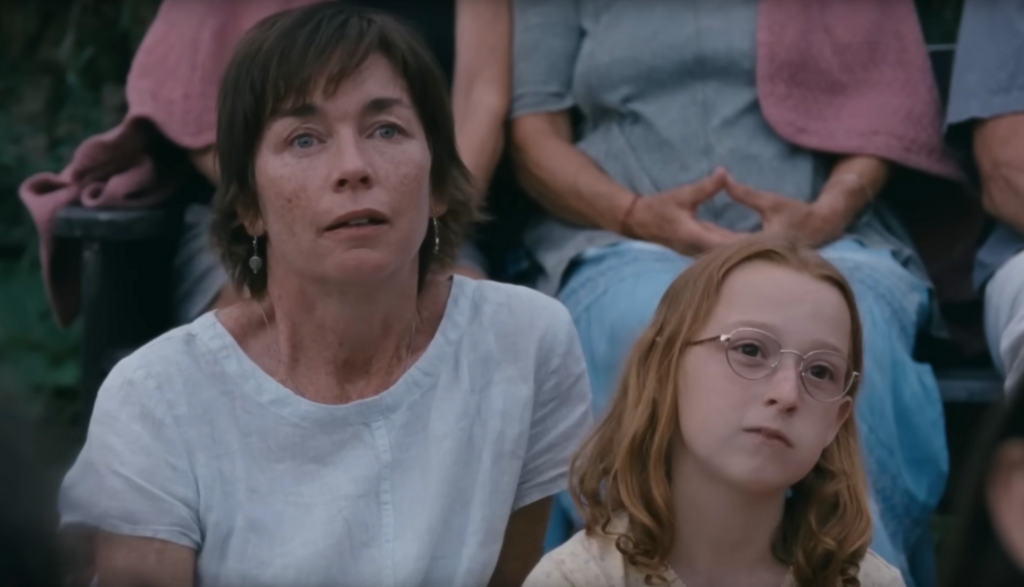

About midway through the film, Lacy and Janet attend an odd outdoor theatrical performance. It’s filled with various metaphysical musings, and Avi (its organizer) describes the event as more akin to a “religious service” than theater. Avi explains that his troupe’s works are preoccupied with the “funereal,” while still being “celebratory.” He talks plenty more about the quasi-religious aspects of the work (though it can sound a bit like he’s just stringing five-syllable words together randomly) while also insisting that impersonal love is the greatest religious impulse we humans have. And then he encourages people to take home a zucchini or two.

Janet mentions that Avi’s theater troupe is considered a “cult” by some, which she defines to Lacy as a group that lives apart from society and seems to worship, or nearly worship, its leader. Avi’s troupe does indeed live on a sort of commune (a farm on which they grow that zucchini), and Avi has plenty of spiritual musings to offer. He doesn’t need to be asked twice—or even asked at all—to offer them.

For instance: One night, Avi has dinner with Janet and Lacy, and he explains the nature of creation to them both. He references the “something” from “nothing” concept of the Big Bang theory, calling the instigator of creation “God, or Brahmin, or whatever you want to call Him.” He describes how God would’ve been sitting on his hands for billions of years before suddenly getting the bright idea to create—then sitting around for another billion or so years before considering the act of creation again.

And then, somehow, he jumps to the idea that we are all gods, something that’s implicit in the act of creation, he says. He singles out Lacy especially. And while it can be difficult to parse exactly what Avi means, it seems he’s not just arguing that we create, therefore we have a god-like impulse in us; rather, we were God, spurring on the Big Bang.

Lacy seems unimpressed, but some of these thoughts resonate with Janet. During a walk in the woods, Janet talks to Lacy about some of her own theosophical musings, piecing them together literally step by step. She talks about how, for instance, someone should pursue “truth beyond self-image,” and then she talks about engaging in a series of “prostrations.” At that moment, Janet literally kneels down and ultimately lies on her stomach, arms outstretched over her head, as she recites this wisdom like a mantra.

Later, Lacy opens the curtains to her figurines and prostrates herself before them. It is, perhaps, a mimicry of her mother, but it certainly can look as though she’s bowing down before her dolls.

As mentioned, Janet is an acupuncturist, a system of healing that is rooted in traditional Chinese medicine and can come with some related spiritual components. We hear that Janet’s father was a Holocaust survivor. As mentioned, one of Lacy’s figurines is a little Buddha statue. Avi makes a couple of references to Buddhism specifically.

Late one night, Janet tells Lacy that she feels she always had the power to get any man to fall in love with her if she really tried.

“Can you stop?” Lacy asks. “Trying.”

Whether she stops or not, Janet has two suitors here. Wayne begins the movie as Janet’s live-in boyfriend. Lacy spies him in bed with Janet, both sleeping soundly, but various arms and legs jutting out from the covers. Later, Lacy catches Wayne dancing and gyrating, apparently naked (though we only see him from the waist up). We also see him in boxer shorts and a T-shirt.

Later, Janet and Avi apparently start dating. The two hold hands while walking through a room filled with Avi’s oversized theatrical “puppets.” Later, they apparently go on a picnic together—a rare date without Lacy present—and Avi reads Janet poetry as he lays his head in her lap.

Janet and friend Regina share a long hug, and Regina lies her own head on Janet’s stomach at one juncture. That said, the two appear to be simply close-but-platonic friends.

Meanwhile, 11-year-old Lacy is beginning to wonder about her own sexuality. She spends a pleasant afternoon with Sequoia, Wayne’s daughter, and the camera zooms in on when Sequoia gives her father a peck on the cheek—perhaps illustrating Lacy’s own focus on that moment of minor intimacy. (They also read together a passage from the racy book The Valley of the Horses, involving kissing.)

Later, Lacy asks Janet whether Janet would be disappointed if Lacy had a girlfriend one day. Janet says that she’d never be disappointed; that she’d sometimes wondered whether Lacy might become a lesbian, because of her rather aggressive personality. (Lacy takes a bit of offense at the presumption that she necessarily would be a lesbian—strongly suggesting that the jury may still be out regarding which gender she might ultimately prefer.)

Regina heads to the bathroom in a towel. Some of Janet’s outfits can be a bit diaphanous. A painting on Janet’s wall seems to depict the stylized back of a nude woman.

Wayne suffers what Janet describes as a migraine headache. Janet tries to treat it with acupuncture, and we see needles sticking out of Wayne’s body. It doesn’t seem to work. Later, a still-hurting Wayne demands that Lacy leave him alone. When Lacy continues to talk within earshot, Wayne storms toward the doorway (where Lacy stands) and slams the door in her face. No one’s hurt, but it feels violently aggressive.

When Janet finds a tick on Lacy’s neck, Lacy tries to smash the insect a couple of times. Alas, it survives. When Janet lights a match to burn it, she hesitates. Lacy takes the burning match out of Janet’s fingers and presses it against the critter, shouting, “Die, tick! Die!”

Cults are often marked by their propensity to keep people in the group by cutting off outside contact and not allowing them to leave. We see hints of that dynamic in Regina’s relationship with Avi; nothing violent occurs, but Avi eventually does take Regina away (presumably back to the farm). And another member of Avi’s troupe later goes to Janet’s house to pack up the rest of Regina’s things.

Lacy threatens suicide if Janet doesn’t whisk her out of what appears to be a nice summer camp. The plea works; Lacy lies to her counselor and campmates, telling them that her Mom’s boyfriend has been hurt in a car crash.

Regina contemplates spontaneous human combustion.

One f-word and one misuse of God’s name. Lacy tells her mom that her life is “h—,” using that word a couple of times.

Regina and Janet use Ecstasy. Regina tells Lacy that the pill she gives Janet will help her sleep, but it does quite clearly the opposite; the two engage in a long night of navel-gazing talk that turns a bit confrontational.

Avi brings over a bottle of wine for dinner. (We see Avi and Janet drink part of it.) When Lacy spies Wayne gyrating in the nude, Lacy reports it to Janet—telling her there’s something “wrong” with him. Janet later tells Lacy that he has a migraine, but it feels as though Wayne might more likely be suffering from a whale of a hangover, and the dancing can be chalked up to what gave it to him.

On the first day of school, Lacy seems to get sick. We don’t see her vomit, but that’s the primary symptom she reports: Either she’s faking it so she doesn’t have to go to school, or she’s so nervous about going that she truly did get sick. We see the girl bent over a toilet and, later, lying on a couch with a plastic bag in her hand.

Lacy also uses the toilet; nothing critical is seen, but Regina (who’s waiting for the home’s sole bathroom) reports that she’s been in there for 45 minutes. Lacy takes a shower and spreads a chunk of her own hair on the shower wall.

“Sometimes, I feel like [Lacy’s] watching me,” Janet confesses to someone.

And indeed Lacy is. As indeed all children watch their parents.

At first, they watch us in the best of ways. They watch how we smile and when. They watch what we say and how. As our young kids get their society-legs under them, we teach them how to walk, how to eat, how to dress, how to behave. We’re their first role models.

But eventually—often right around Lacy’s age—they begin to see that we’re not quite who they thought we were. Not quite what we’d like to be. They might notice inconsistencies. Weaknesses. When we get mad, it’s not always their fault; sometimes it’s ours.

Janet Planet is, in some ways, a story about that time of transition. But it’s both more than that, and less. It’s a movie where very little actually happens. And yet, I walked out of the theater inexplicably sad.

I still can’t quite put my finger on why. But I wonder if it’s rooted in the relationships we see here, or lack thereof. How everyone seems so eager to know, so eager to be known—and yet they never quite get there.

Even Janet and Lacy’s relationship is vexing. On one hand, they’re as close as mother and daughter can be. But that very closeness can, paradoxically, feel exasperating too. Because for all of the time they spend together, all the space they share, Lacy and Janet’s orbits are unique and solitary. United and divided.

We all long for connection. And yet, ultimately—in this world, at least—we often feel very alone.

Janet Planet is filled with lonely people struggling for connection, for understanding, for transcendence. This story, which takes place in the same state Henry David Thoreau wrote Walden, is filled with people living lives of, in Thoreau’s words, “quiet desperation.”

Outside of the movie’s hippie vibe and Avi’s transcendental musings (which even the movie itself doesn’t necessarily take all that seriously), we don’t have a lot of content to navigate here. An f-word slips once. Lacy’s clearly aware of Janet’s male suitors. But primarily, we see this world through Lacy’s eyes, and Janet—conscientious, guilt-ridden mother that she is—tries to keep Lacy’s world relatively innocent.

But while we gain entrance to Janet Planet through a child, the movie itself is not for children, nor would it likely interest them. This character study is both poignant and perplexing—as frustrating at times as parenthood itself can be, and without its unbridled joy.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.